Mary Ward’s Story

“That incomparable woman whom Catholic England, in her darkest and bloodiest hour, gave to the Church”

Pope Pius XII

Born into a Yorkshire Catholic recusant family in 1585 Mary Ward was remarkable for being one of the first women to believe that women should be actively involved in the apostolic life of the Catholic Church. However, initially she opted for the strictest form of contemplative religious life determined to give herself totally to God. For this she went to St. Omer in Flanders where she joined the Poor Clare Order as a lay sister.

When God revealed to her that a life of prayer and obscurity behind a convent wall was not what she was called to, she returned to London in 1609. Here, with a group of like-minded young women, she engaged in apostolic work disregarding the strict laws against Catholics at the time. Later that same year Mary realised that God was calling her to some form of religious life “more to His glory”. To discern what that might be, she left London for Flanders with her young companions and founded her first house at St Omer.

In 1611, whilst at prayer, enlightenment came to her and she heard clearly the words: ‘Take the same of the Society, by which she understood the ‘Society of Jesus’ founded by St Ignatius of Loyola. The rest of her life was spent in developing a congregation of religious women on the Ignatian model. For this, she needed, and repeatedly failed to gain, Papal approval.

Three times she and her companions walked to Rome from Flanders, over the Alps, twice to try to gain this approval and the third time as a prisoner of the Inquisition following the suppression of her congregation by Pope Urban VIII in 1631. During this period she founded houses and schools in St. Omer, Liège, Trier, Cologne, Rome, Perugia, Naples, Munich, Vienna and Pressburg (Bratislava), often at the request of the local rulers and bishops, but Papal approval eluded her.

To the Papal authorities, a congregation of apostolic, unenclosed, self-governing women was unthinkable at a time when the reforms of the Council of Trent had forbidden new religious congregations and confined religious women to enclosure. Had she been prepared to compromise and accept a form of enclosure Mary might have obtained Papal approval. However, she would not compromise and preferred to face the dissolution of her congregation, imprisonment, the imputation of heresy, and disgrace rather than abandon her conviction that “there is no such difference between men and women that women may not do great things … and I hope in God it will be seen, that women in time to come will do much.”

Summoned to Rome in 1632 to face charges, Mary was granted an audience with the Pope at which she declared: “Holy Father, I neither am nor ever have been a heretic”. She received the comforting reply: “We believe it, we believe it”. No trial ever took place, but Mary Ward was forbidden to leave Rome or to live in community.

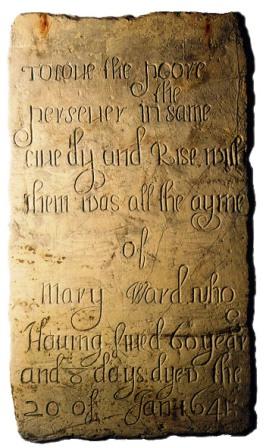

In 1637, for reasons of health Mary was allowed to travel to Spa and then on to England. She died during the English Civil War just outside York on 30 January 1645. She is buried in the Anglican churchyard of Osbaldwick just outside York.

The Ongoing Story

“All that is not in Him and for Him will pass away with time”

Mary Ward

The 1631 Bull of Suppression destroyed Mary Ward’s first institute. However, it did not destroy the will of her companions to persevere in the form of the unenclosed, apostolic religious life to which Mary and they had felt called. The history of the survival, growth, and recognition by the Church of Mary Ward’s founding vision is a long and complicated one.

The same dilemma that faced Mary Ward in her lifetime faced her successors, namely, how to be loyal to a Church that refused to recognise the right of the congregation to exist whilst at the same time striving to be faithful to that founding vision. That the institute survived at all is remarkable, and a sign that the Church needed an institute such as Mary Ward’s without actually realising it.

By the end of the 17th century the institute was well established in Bavaria in Munich, Augsburg and Burghausen, and was about to expand into the Habsburg dominions. It also had a foothold in England in London and York. Compromises were inevitable in order to survive. In many instances, houses became semi-monastic in their life-style, but the educational apostolate continued to flourish. Most significantly, the memory of Mary Ward lived on, despite the second Bull of 1749 that re-emphasised the prohibition on recognising her as a foundress. Many of her letters and other historic material were destroyed, but the memory of what she had wanted lived on. An interesting letter from the early 18th century notes: “Ours keep faithfully … to the approved rules as well as to all those regulations that are not approved”.

By the early 19th century it was becoming more acceptable for women religious to be apostolically active in the Church. With the rise of liberalism and socialism the need for an educated Catholic laity was recognised. This was also the period of missionary activity and the institute spread throughout Europe and overseas to India. In 1877 the Institute of the Blessed Virgin Mary, as it was then known, was at last approved by the Church, but not with the full Ignatian Constitutions for which Mary Ward had struggled. That had to wait another century until the reforms of the Second Vatican Council encouraged religious to return to the charism of their founders.

In 1909 Mary Ward was at last recognised as the foundress of the Institute of the Blessed Virgin Mary, but it took another century before her sisters were at last able to “take the same of the Society”. This did not take effect until the General Congregation of 2002.

The complex history of Mary Ward’s foundation over the past 400 years gave rise to a series of separate houses and Generalates at different times. At present there are two branches of her institute: the Congregatio Jesu and the Institute of the Blessed Virgin Mary, also known as the Loreto sisters, founded in Ireland from York in 1821 As is mentioned elsewhere, these two remaining branches of Mary Ward’s Institute are in the process of becoming one.

On Pilgrimage with Mary Ward App